Governance Surveys

Directorship Magazine

Online Article

Consider Retirement Provisions to Aid Retention and Succession Planning

In the United States, individuals born between 1946 and 1964 are hitting peak retirement age. Those in this group hold many executive positions in public and private companies, creating a risk of loss of institutional knowledge and potential business disruption as they retire. Some companies may be facing the opposite problem: lingering executives who should retire to create opportunities for advancement for the next generation of leaders.

In either case, examining retirement provisions included in compensation programs should be part of every company’s retention and succession strategy. The right provisions can help a company either move executives on or keep them in place until the next generation of leaders is ready.

Market Practices for Retirement Provisions

Time-Based Awards Treatment

Retirement provisions for time-based awards that require service only for vesting are generally more straightforward than other types of awards.

Source: National Association of Stock Plan Professionals-Deloitte Consulting LLP 2024 Equity Incentives Design Survey

Most companies—roughly 61 percent according to the National Association of Stock Plan Professionals-Deloitte Consulting LLP 2024 Equity Incentives Design Survey—provide some additional service credit at the time of retirement, whether it be pro rata, full acceleration of vesting, or continued vesting. Thirty-six percent of companies in the survey reported immediate forfeiture of time-based awards and 3 percent of responding companies explicitly leave the retirement treatment up to board discretion.

Performance-Based Awards Treatment

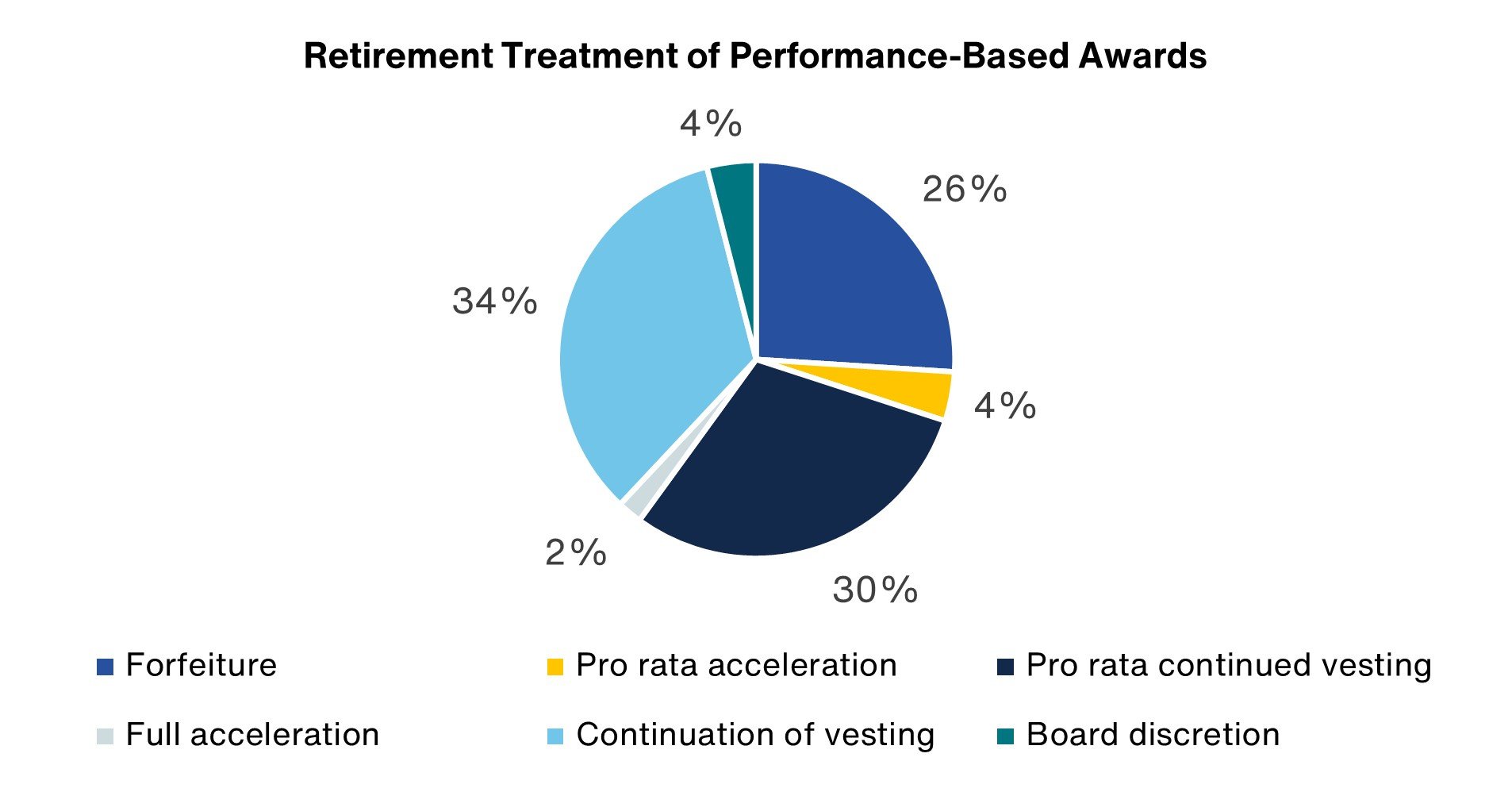

There are four major treatments of performance-based awards at time of retirement, as described in the survey:

- Thirty percent of surveyed companies allow a pro rata portion of the awards (based on service completed during the performance period) to vest, typically based on the actual performance at the end of the period.

- Thirty-four percent allow the full award to continue to vest according to the original vesting schedule, based on the actual performance at the end of the period.

- Twenty-six percent forfeit awards entirely.

- Four percent explicitly maintain board discretion.

Source: National Association of Stock Plan Professionals-Deloitte Consulting LLP 2024 Equity Incentives Design Survey

While boards always maintain discretion, whether explicitly stated or not, a discretionary approach can be externally viewed by proxy advisors and institutional investors as problematic. One of the primary reasons for this is that, at times, senior level departures are characterized as “retirements” that come with additional, noncontractual payments of severance or additional vesting. These can be perceived as payment for nonperformance and create say-on-pay and other shareholder relation issues.

The Executive’s Point of View

Executives usually have a considerable amount of unvested equity at any given moment. Naturally, no one wants to forfeit these awards or money. As a result, executives without any additional retirement vesting provisions may be incentivized to stay on longer than optimal for the company.

Most equity incentives are long-term in nature, whether time-vested (typically a three- to four-year vesting period) or performance-vested (typically a three-year performance cliff). As a result, there are often large portions of equity that have not vested due to the design of the awards. In the example below, the employee will always have unvested equity on the table due to the timing of new grants and the way that the vesting occurs over time.

The Company’s Point of View

It can be useful to provide continued or pro rata vesting for time-based equity awards and pro rata vesting for performance-based equity awards (at the end of the performance period based on actual performance) for the following reasons:

- These awards promote the retention of executives through retirement eligibility.

- They lead to a smoother discussion if the company wants to request that an individual consider retirement.

- They allow the company to attract mid- to late-career talent, who could potentially meet the definition of “retirement eligible” through their age or their age plus relatively short service (a combination of age and service equal to 70 years is often a definition of retirement eligibility; for example, an eligible individual could be 65 years old with five years of service).

- They incentivize executives to be open about their retirement plans, as executives won’t risk immediate forfeiture of their equity awards or fear of dismissal followed by forfeiture.

- The continued vesting post-retirement provides recognition of the long-term impact of a leader’s decisions, including decisions that impact the company and shareholders post-retirement in many cases.

The Board’s Point of View

Board members can, and should, inquire about retirement provisions during succession planning discussions and as new equity awards are contemplated and approved.

While there are accounting cost implications of changing these vesting provisions (and it is likely advisable to consider doing so for future awards only), modification of these provisions can be a very effective executive talent recruiting, retention, and succession-planning tool at a time when executive talent is scarce and aging.

Additional Considerations for Retirement Provisions

While the aforementioned treatments can assist companies in managing workforce transitions, there are further considerations to prevent any potential downstream effects. The primary reason many companies refrain from incorporating retirement provisions into their equity programs is the need to accelerate unamortized compensation expense once awards become nonforfeitable, as mandated by accounting standards. For example, compensation expense can only be amortized over the period during which the awards remain forfeitable. With an aging workforce, many companies have sizable populations that would meet the definition of “retirement eligible,” often at more senior levels of the organization and with larger award sizes, which means that the acceleration of unamortized compensation expense for those individuals could be significant.

That said, there are multiple tools and design considerations for companies to consider in order to make the acceleration of expense more palatable. For instance, some companies have leveraged minimum service periods, or even substantive notice periods, on awards to receive the retirement benefit, which can allow some continued amortization of expense. Others have considered only providing a prorated portion of the award tied to when the individual retires, which can also allow some continued amortization of expense. Furthermore, those that allow full, continued vesting may create an implied holding period, for which the fair value of the award can be discounted for the period of illiquidity. This does not prevent the expense from being accelerated, but it can lower the total expense recognized.

While retirement provisions in equity compensation might seem like a micro point in a macro environment, considering an employee’s total rewards, potential leverage in the company’s stock versus a diversified portfolio of retirement assets, and their perception of readiness to retire involves more complex measurements, decisions, and considerations. Ensuring that the retirement provisions existent in the compensation programs reward for desired behaviors rather than inadvertently cause the opposite is something that should be monitored over time and always adapted to. To attract, retain, and motivate top-tier talent, companies should tailor their strategies to shifting macroeconomic conditions, industry-specific regulations, and evolving workforce demographics. Well-designed retirement plans can be a powerful tool in achieving these objectives. Do not forget to involve finance and accounting experts early in any decision-making process as the complexities are myriad.

Aon is a NACD partner, providing directors with critical and timely information, and perspectives. Aon is a financial supporter of the NACD.

Amanda Benincasa Arena is a partner with Aon’s Equity Services Practice.

Theo Sharp is a partner with Aon’s Executive Compensation Consulting Practice.

Calista Kelso is a senior associate consultant with Aon’s Equity Services Practice.